Story and photos by Tony Mangia

Like most of the world, I was watching on February 24, 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. The chaos might have been a world away, but it was still hard to watch millions of innocent Ukrainians suddenly become victims and refugees from their own homes as they made their way towards camps in Hungary, Poland and Romania.

Carrying only what what they could stuff into their cars or tote in their suitcases, this humbled mass of humanity made its way through the winter cold along the treacherous routes to nearby welcoming countries and the unknown. The image of fear and trepidation played out in the photos of the refugees lining the roads leading out of Ukraine. And, as Putin’s aggressions mounted, there seemed like it was the only one choice to guarantee the safety of their families.

Those images are hard to forget.

Now, nearly three months later, many of those same asylum seekers are going home. They are hopeful, but wary, not knowing how this war will end. Over that span, the refugees have had plenty of time to ponder and find numerous reasons to head back home despite the dire circumstances. Some because of financial hardship, some because they missed family members who stayed behind and others to lend a helping hand in the fight against Russia.

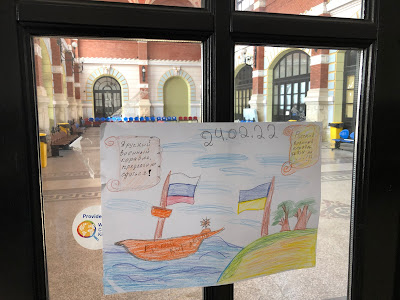

|

| A child's rendering of the Russian invasion in a drawing. |

The stress of being displaced to a strange country, the feeling of helplessness or the touch of a familiar hand had become too much of a sacrifice despite the risks of going home. It’s hard to imagine that pain of coping with isolation from loved ones — many who are still within firing range of Russian artillery.

Now that Vladimir Putin has concentrated most of his aggression on the eastern border, many brave Ukrainians are returning to their families in Kyiv, Lviv and central sections of the country despite the hazards.

It takes courage to fight a war on the front, but it takes just as much fortitude and resilience to return home to one. You might call it the Ukrainian civilians’ version of the Snake Island “Go f—k yourself” to Putin.

In May — almost three months after Putin’s aggression, I had just finished working with a volunteer program in Romania when I started meeting groups of Ukrainian refugees (all women and children) who were returning home.

|

| Volunteer helping out at Suceava train station. |

Sitting among the local men — an out of the ordinary number of them nursing morning beers — I sipped a coffee looking out at the ornate light fixtures silhouetted against a clear blue morning sky at the Suceava train station. Among the normal commuters, I noticed some groups bustle about the terminal platforms and get on specially marked buses in the parking lot.

Suceava, I found out, is the last train stop before a highway threads its way alongside the eastern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains through golden fields of sunflowers leading to Siret — one of the seven major entry points into Romania and a border town once flooded with tens of thousands of refugees after the invasion by Putin’s army.

|

| The road to Siret from Suceava. |

The Suceava train station has now become a major junction where Ukrainians make one of the final transportation links back to their homeland.

|

| The Suceava train station. |

Lumbered down with large tote bags and suitcases, some of the nearly 900,000 Ukrainians who became refugees in Romania board buses back to their crippled cities. Mostly women and children, there are also throngs of day trippers coming from Ukraine to purchase food and other supplies which are scarce or too expensive there.

While there are so many singular narratives pertaining to the Ukraine invasion and the fighting, lost among the depressing headlines are the personal accounts of the refugees, activists and volunteers whose lives have been affected by the war.

Here are a few of their shortened individual stories as refugees, their journeys back home and what they see in their futures:

Slava was a woman I met at the refugee welcome center at Suceava train station. She seemed anxious knowing the border of Ukraine — which is about 25 miles north as the dove flies — was within reach. She was returning to her homeland after 77 days in Romania. A two-hour bus ride from Suceava was the only thing standing in the way of touching Ukrainian soil for the first time in months.

|

| Slava at the World Central Kitchen kiosk. |

As Slava waited for the mini-bus home, Father Nistor was handling the chores at the center this day. Working with the World Central Kitchen, the Romanian Orthodox priest was happy to dole out supplies and faith in equal measures. Father was also thrilled to call his wife who wanted to talk with me, an American, in English. Sandwiches, bottles of water, snacks along with directions and language translations were provided to anyone who asked.

|

| Orthodox priest, Father Nistor, is one of many volunteers helping Ukrainian refugees return home. |

A defiant Slava did not know exactly what she would be returning to, but her homesickness overcame any fears of Russian occupation. Slava was lucky enough to work for an American-owned company in Ukraine that paid her salary while she was away.

“We are thankful for the world’s support and donations,” she said.

Tania— a 26 year old from Dnipro a city about 100 miles northwest of Mariupol — left her hometown when the Russian made advances towards it. She worked as civil activist in Ukraine and is passionate about her hate of Russia and how she wants to help out her volunteer boyfriend and mom who are still there.

“There was a lot of talk about nuclear bombs before I left,” she said. “We didn’t know what to expect.”

|

| Tania reflects on her future in Ukraine. |

Tania is now working as a project assistant for an NGO raising money and making contacts with other charitable groups who help out.

Kateryna is a 32 year-old friend of Tania who was first “going home” to the Kyiv region before leaving to lend a hand to the military.

“Nervous, but I’ll do what I can do to help,” the self-described activist said.

Kateryna remembered the bombs she heard in Kyiv before she left.

“You could distinguish the difference between the ground and air bombs and where they would land,” is how she described the bombardment on the northern front.

I’ve been in contact with Kateryna — while she in Zaporizhhya, a city about 100 miles from battle weary Mariupol. She is working with Mainstream — a community NGO raising money for bulletproof vests, helmets, food and medicine for the army. They have very successful, but the group has a giant task in front of them.

|

| Kateryna at Suceava train station. |

“We are trying to find money and buy things for the army,” she said, briefing me on her work. “And I’ve been training civil activists.”

Kateryna has kept me up to date with her progress and proudly showed me photos of the supplies they collected at the volunteer hub for ibashorcs.xyz which also supplies technological needs for the Ukraine military.

|

| Soldiers and soldiers get new supplies. |

In the train station I meet Anna, the mother of two young children — a boy dressed in yellow t-shirt and blue hat reflecting the now well-known colors of the Ukraine flag and his little sister who was cradling a stuffed toy. They were going back home after two months in Romania with their grandmother, Liliana, because her children simply “miss their father” who stayed behind to work.

“They are not scared,” she said about her children as they boarded a small transport van on the first leg of their journey back home.

It's hard not to be impressed by their humble—yet brave—determination.

|

| Anna, her children and Liliana want their family whole again. |

I met Inna in the train station parking lot boarding bus to Ukraine with two young boys and friend Alina. They were making a connection back to where husband stayed behind in Kyiv after living two months in a free apartment in Romania. Alina fled Feb 24 to Romania after the bombs started. They are headed to the Ukrainian border town of Novoselytsia where her parents ( who were too elderly to leave) remained.

“We are not brave,” said Inna, way too modestly. “We are far from where they are fighting.”

|

| Inna returning home to husband and young sons father. |

Katryna was returning to Black Sea area of Odessa where her husband is in the Ukraine navy. She left in February and plans to go back and help out as a food distribution volunteer. Like so many Ukrainians at the train station, she is rolling a giant suitcase full of food supplies alongside Natalia, an older woman she just met.

“The cost of food is too high where I live in Ukraine,” says Natalia.

|

| Two new friends, Katryna and Natalia, with common goal of returning home. |

Katryna forces a cynical laugh when she tells me she’s normally a travel agent back home near Kyiv.

“Not many people vacationing in Ukraine right now,” she says in pretty good English.

“I’m not sure if it was right thing to do,” she says about leaving Ukraine herself, “But if there are too many bombs, I might return to Romania.”

Some, like Yulia, are debating whether or not to return home. The 19-year-old student has spent almost three months in Romania with family after fleeing from Kharkiv, a city north of Kyiv bordering Russia. Yulia told me that she spent five days in a neighbor’s cellar with her family listening to the bombs fall after February 24.

“We saw bombs and I was little scared,” Yulia recalls, “And then my family told me to leave.”

She recounts her childhood friendships with nearby Russians who she feels she will never speak to again. She gets emotional while showing me graphic photos of the atrocities inflicted on the Ukrainians in Bucha on her phone—one which appears to be a naked female body stuffed down a sewer pipe. It's a horrible depiction of war that I hope I can eventually erase from my mind.

“They are the enemy now,” she says with a somber tone.

|

| Yulia gets emotional looking at videos of her family back home. |

Yulia then tears up showing me videos of her five-year-old brother dancing around the barren cellar they sheltered in.

“I still have high hopes for the future of our country,” she says while looking at the last grim reminders of home.

Later, I meet Yulia with Daniel, a fellow student from Moldova studying in Romania with whom she has become friends with. Together they excitedly take me on a short taxi ride through Suceava and introduce me to a Ukrainian swim coach who is helping teenaged refugees continue their athletic training at a local university — some with aspirations of competing in the upcoming European Championships this summer. For now they compete against Romanian teams.

|

| Daniel and Yulia reflect on their situation. |

Sidletskay Liudmila haș been coaching in Romania for four years, but because of the war has taken the refugee swimmers under her wing. Inside a modern swim facility on the University cel Mare Suceava campus, I meet two of the young athletes who call themselves professional swimmers and came to Romania when the familiar smell of pool chlorine had been overcome with the stench of gun powder.

|

| Sidletskay (arm raised) and the Ukrainian swimmers. |

Ihor is 17 and, in an era of teenagers’ historical context seemingly only going back to the last big trending moment, he surprised me by saying Mark Spitz his hero. He and his 16-year-old teammate, and “Super professional,” Timur, both have eyes on the 2024 Olympics.

“I don’t know when we’ll go back, maybe next year,” says Ihor — his words slightly echoing inside the cavernous pool area. “I don’t know what the future holds, but we will be representing Ukraine.”

|

| Timur and Ihor still have high hopes for their futures. |

At least having a dedicated coach and and a place to workout, both can keep their athletic dreams alive.

In February and March, when millions left their battle-torn cities and suburbs to find safe haven for their families, the border at Siret was filled with confused refugees. The large temporary city of tents which once gave shelter to the new arrivals has been whittled down to dozens of canopied volunteer outlets offering food, goods, advice and medical help through organizations from around the world.

|

| Numerous charitable organizations and volunteers have been mobilized at the Ukraine border. |

It is now less hectic and looks more like a row of boardwalk concession stands, although one could easily imagine the chaos last winter when the sudden arrival of thousands jammed the border without the ability to communicate, the knowledge of where they were going and a lack of food or amenities adding to the confusion. As you walk alongside the cars lined up to reenter Ukraine, you can still sense the ghosts of desperation and fear when the war first started.

|

| Beds in a refugee medical tent still remain in Siret. |

That mass migration out of Ukraine ended months ago, but thousands of Ukrainians are still crossing the border daily by foot, bus and car mostly to buy supplies and return. Five miles of eighteen-wheelers carrying supplies lined up bumper to bumper at the Siret border check point into Ukraine is testament to the short supply of goods. It’s a giant mechanical centipede that slowly slithers up along the shoulder of the narrow road — a maddening procedure where stoic drivers basically live in their cabs and repeatedly crank their their diesels only to move a few hundred feet one turn of the key at a time. I noticed semis stamped with Turkish, Danish and German — among other European countries — trucking company logos within the convoy — many emblazoned with the yellow and blue Ukraine flag as well.

|

| Nearly five miles of supply trucks wait to enter Ukraine from Romania. |

The drivers all told me they have been in this monotonous queue for at least three days while their shipment is inspected by soldiers and police. The line of empty trucks leaving Ukraine on the other side to reload was just as long.

|

| Stoic truck drivers wait their turn in line. |

In Chernivtsi, a bustling Ukraine city of over 250,000, there is little to remind one of the war blazing hundreds of miles east and only about 100 miles north except for shops filled with anti-Putin t-shirts, the occasional anti-Russia graffiti and the abundance of flapping Ukraine flags. In all outward appearances, life seems to go on as normal, but hidden away in many buildings, behind-the-scenes war relief efforts are ongoing.

There is a sense of urgency and importance at UK-Med — an humanitarian organization based in Manchester, England — where a loaned out third floor gym of the Bukovyna hotel across from woodsy Zhovtnevyy Park serves as a temporary headquarters.

It’s here where I met Nataliya — a “lawyer” who left Kyiv and now works as a translator for the organization which sends doctors and nurses to natural and manmade disasters. Nataliya wouldn’t go into details, but said she left her position as a “high justice council” to assist in the Ukraine medical war effort. She is one of the thousands of Ukrainians who gave up the life they knew either out of necessity, fate or just the will to defeat Putin’s mad assault on their country.

“I am not sure when I will return to Kyiv,” she said. “There is work to be done here now.”

|

| Daytrippers make their way across Siret border to buy goods which are scarce and more expensive in Ukraine. |

The headlines seem to flip-flop daily — whether it’s Russia escalating their bombing or the Ukrainian army pushing the invaders back. Regardless, peace seems a long way off and transplanted Ukrainians know it’s time for action even while the shrapnel and bullets fly.

It’s the need to make their family units whole again or help the war effort in some way that has spurned a movement to not idly sit back and watch from another country. In all of the faces of the Ukrainian people I met in Romania and Ukraine I sensed a war-weary fatigue inside, contrary to the determination and glimmer of hope I saw in their eyes.

It will be a long, perilous road to recovery, but now that Ukrainian refugees are carving small paths back, it’s a start.

The blog's dedication to sourcing and citing reputable references contributes to its credibility. Also check out the murrieta courthouse

ReplyDelete