Story and photos by Tony Mangia

Like most of the world, I was watching on February 24, 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. The chaos might have been a world away, but it was still hard to watch millions of innocent Ukrainians suddenly become victims and refugees from their own homes as they made their way towards camps in Hungary, Poland and Romania.

Carrying only what what they could stuff into their cars or tote in their suitcases, this humbled mass of humanity made its way through the winter cold along the treacherous routes to nearby welcoming countries and the unknown. The image of fear and trepidation played out in the photos of the refugees lining the roads leading out of Ukraine. And, as Putin’s aggressions mounted, there seemed like it was the only one choice to guarantee the safety of their families.

Those images are hard to forget.

Now, nearly three months later, many of those same asylum seekers are going home. They are hopeful, but wary, not knowing how this war will end. Over that span, the refugees have had plenty of time to ponder and find numerous reasons to head back home despite the dire circumstances. Some because of financial hardship, some because they missed family members who stayed behind and others to lend a helping hand in the fight against Russia.

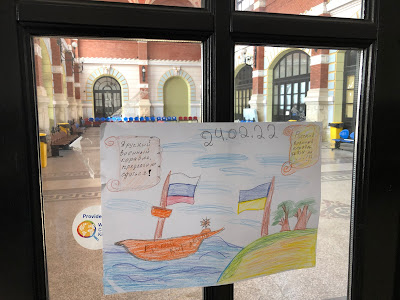

|

| A child's rendering of the Russian invasion in a drawing. |

The stress of being displaced to a strange country, the feeling of helplessness or the touch of a familiar hand had become too much of a sacrifice despite the risks of going home. It’s hard to imagine that pain of coping with isolation from loved ones — many who are still within firing range of Russian artillery.

Now that Vladimir Putin has concentrated most of his aggression on the eastern border, many brave Ukrainians are returning to their families in Kyiv, Lviv and central sections of the country despite the hazards.

It takes courage to fight a war on the front, but it takes just as much fortitude and resilience to return home to one. You might call it the Ukrainian civilians’ version of the Snake Island “Go f—k yourself” to Putin.

In May — almost three months after Putin’s aggression, I had just finished working with a volunteer program in Romania when I started meeting groups of Ukrainian refugees (all women and children) who were returning home.

|

| Volunteer helping out at Suceava train station. |

Sitting among the local men — an out of the ordinary number of them nursing morning beers — I sipped a coffee looking out at the ornate light fixtures silhouetted against a clear blue morning sky at the Suceava train station. Among the normal commuters, I noticed some groups bustle about the terminal platforms and get on specially marked buses in the parking lot.

Suceava, I found out, is the last train stop before a highway threads its way alongside the eastern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains through golden fields of sunflowers leading to Siret — one of the seven major entry points into Romania and a border town once flooded with tens of thousands of refugees after the invasion by Putin’s army.

|

| The road to Siret from Suceava. |

The Suceava train station has now become a major junction where Ukrainians make one of the final transportation links back to their homeland.

|

| The Suceava train station. |

Lumbered down with large tote bags and suitcases, some of the nearly 900,000 Ukrainians who became refugees in Romania board buses back to their crippled cities. Mostly women and children, there are also throngs of day trippers coming from Ukraine to purchase food and other supplies which are scarce or too expensive there.

While there are so many singular narratives pertaining to the Ukraine invasion and the fighting, lost among the depressing headlines are the personal accounts of the refugees, activists and volunteers whose lives have been affected by the war.

Here are a few of their shortened individual stories as refugees, their journeys back home and what they see in their futures:

Slava was a woman I met at the refugee welcome center at Suceava train station. She seemed anxious knowing the border of Ukraine — which is about 25 miles north as the dove flies — was within reach. She was returning to her homeland after 77 days in Romania. A two-hour bus ride from Suceava was the only thing standing in the way of touching Ukrainian soil for the first time in months.

|

| Slava at the World Central Kitchen kiosk. |

As Slava waited for the mini-bus home, Father Nistor was handling the chores at the center this day. Working with the World Central Kitchen, the Romanian Orthodox priest was happy to dole out supplies and faith in equal measures. Father was also thrilled to call his wife who wanted to talk with me, an American, in English. Sandwiches, bottles of water, snacks along with directions and language translations were provided to anyone who asked.

|

| Orthodox priest, Father Nistor, is one of many volunteers helping Ukrainian refugees return home. |

A defiant Slava did not know exactly what she would be returning to, but her homesickness overcame any fears of Russian occupation. Slava was lucky enough to work for an American-owned company in Ukraine that paid her salary while she was away.

“We are thankful for the world’s support and donations,” she said.

Tania— a 26 year old from Dnipro a city about 100 miles northwest of Mariupol — left her hometown when the Russian made advances towards it. She worked as civil activist in Ukraine and is passionate about her hate of Russia and how she wants to help out her volunteer boyfriend and mom who are still there.

“There was a lot of talk about nuclear bombs before I left,” she said. “We didn’t know what to expect.”

|

| Tania reflects on her future in Ukraine. |

Tania is now working as a project assistant for an NGO raising money and making contacts with other charitable groups who help out.

Kateryna is a 32 year-old friend of Tania who was first “going home” to the Kyiv region before leaving to lend a hand to the military.

“Nervous, but I’ll do what I can do to help,” the self-described activist said.

Kateryna remembered the bombs she heard in Kyiv before she left.

“You could distinguish the difference between the ground and air bombs and where they would land,” is how she described the bombardment on the northern front.

I’ve been in contact with Kateryna — while she in Zaporizhhya, a city about 100 miles from battle weary Mariupol. She is working with Mainstream — a community NGO raising money for bulletproof vests, helmets, food and medicine for the army. They have very successful, but the group has a giant task in front of them.

|

| Kateryna at Suceava train station. |

“We are trying to find money and buy things for the army,” she said, briefing me on her work. “And I’ve been training civil activists.”

Kateryna has kept me up to date with her progress and proudly showed me photos of the supplies they collected at the volunteer hub for ibashorcs.xyz which also supplies technological needs for the Ukraine military.

|

| Soldiers and soldiers get new supplies. |